From Shenzhen and Seoul to Tel Aviv: CAD/PLM’s Other Epicenters

After tracing PLM’s evolution in the United States and Europe, it would be easy to imagine the story as complete — a tale dominated by the Boston Route 128 corridor, Silicon Valley, Stuttgart, and Paris. Yet that would ignore an equally compelling truth: CAD and PLM are not Western monopolies. Across Asia, Israel, and resource-rich economies like Australia, the ecosystem has taken on distinctive local forms. In some cases, countries nurtured their own geometric kernels and CAM systems. In others, they birthed vertical champions so strong that global players had no choice but to acquire them. This “rest of the world” view reveals how sovereignty, vertical depth, and entrepreneurship continue to shape engineering software far beyond the transatlantic mainstream.

China: Sovereignty Through Software

If Europe has been about integration and America about disruption, China has been about sovereignty. Beginning in the 1990s, Chinese policymakers realized that dependence on Western CAD kernels and CAM systems created a strategic vulnerability. The government began backing domestic vendors, encouraging firms to move from DWG clones toward fully fledged 3D and CAM solutions.

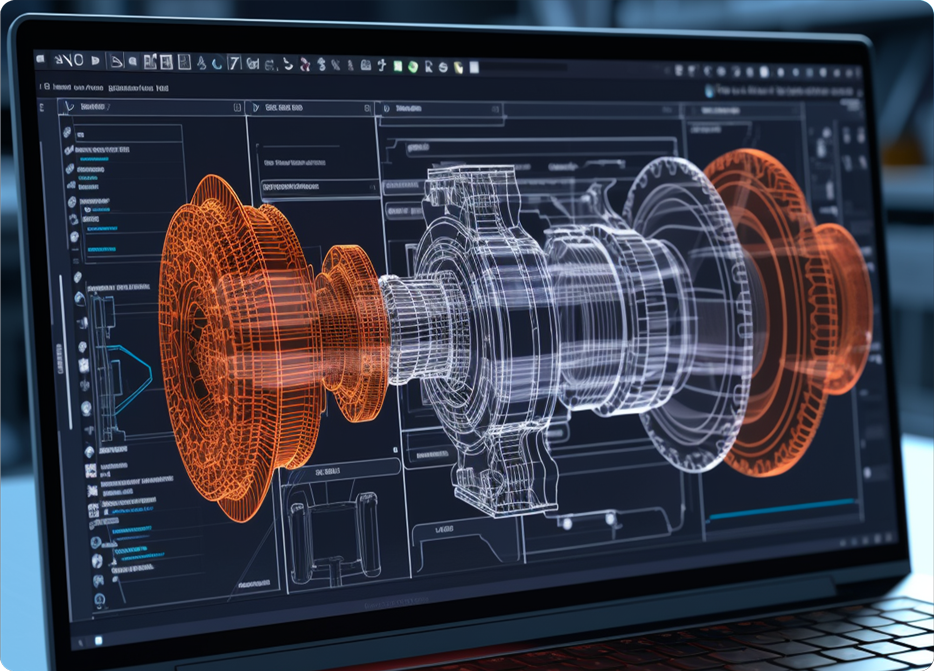

The most prominent is ZWSOFT, headquartered in Guangzhou. What began as a DWG-compatible alternative (ZWCAD) took a decisive leap in 2010 when ZWSOFT acquired VX Corporation of Florida, bringing not only a solid modeling kernel but also an integrated CAD/CAM platform. This became ZW3D, now widely adopted in Chinese aerospace and manufacturing. Alongside, GstarCAD built its own ecosystem of DWG-centric products, while firms like Poisson Software of Shenzhen quietly recruit for 3D geometric modeling expertise — a signal that new kernels may be incubating.

China’s approach is pragmatic: imitate to gain market share, acquire where possible, and gradually build indigenous IP. In the long run, the strategy is less about competing with Dassault or Siemens abroad than ensuring Chinese manufacturers can never be cut off from the digital tools they need at home.

Russia: Kernels as Industrial Policy

Where China seeks industrial self-sufficiency, Russia seeks outright autarky. Since the Soviet collapse, Russia’s engineering software sector has been defined by an insistence on domestic kernels.

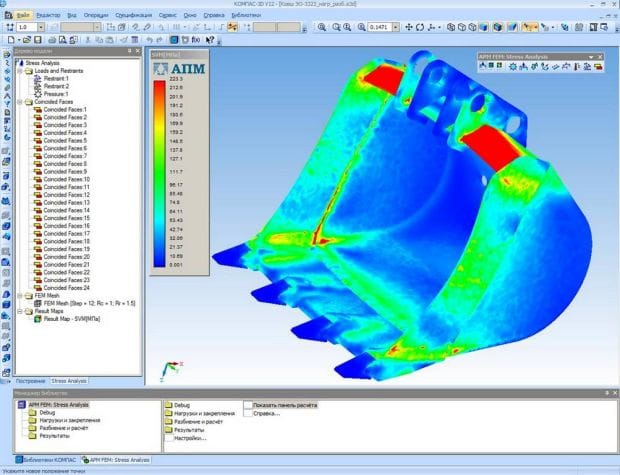

ASCON, through its KOMPAS-3D product, spun out the C3D kernel, now offered as a commercial toolkit (see this article: https://www.linkedin.com/posts/mfinocchiaro_cad-geometricmodeling-softwareengineering-activity-7362045456983416833-t9Q_?utm_source=share&utm_medium=member_desktop&rcm=ACoAAABTmhYB--4z1kd8jhB7eGE93gxPaEFahDo).

In parallel, the Russian government sponsored the RGK project — the Russian Geometric Kernel — developed with support from Top Systems and LEDAS. By 2013, RGK claimed “full-featured” status, but adoption has largely been limited to domestic use.

Sanctions following 2014 and again in 2022 accelerated this inward turn. While C3D Labs markets internationally, its primary role is to ensure Russian industry has access to sovereign geometry. In Moscow as in Beijing, the geometric kernel is not just math — it is national strategy.

Japan: Precision and Knowledge

Japan’s CAD story has always been tied to precision industries — cameras, optics, and automotive. While Western audiences remember SolidWorks or CATIA, Japan quietly produced its own geometry engines. DesignBase, developed at Ricoh, is one such forgotten kernel. See this article for details: https://www.linkedin.com/posts/mfinocchiaro_plm-plmhistory-designbase-activity-7361683098096336898-Iini?utm_source=share&utm_medium=member_desktop&rcm=ACoAAABTmhYB--4z1kd8jhB7eGE93gxPaEFahDo

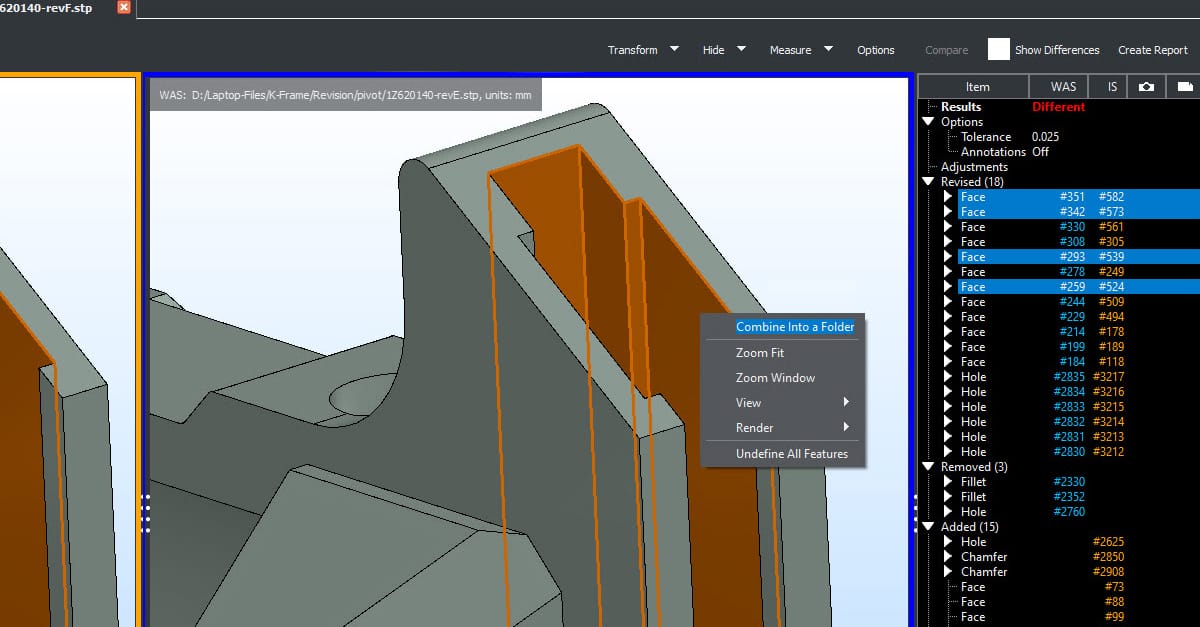

Kubotek, originally Japanese, carried forward the legacy of CADKEY and now markets Kosmos, a modern kernel with a focus on precise translation and interoperability. See this article for more, https://www.linkedin.com/posts/mfinocchiaro_bettercallfino-cad-innovation-activity-7371180724294455297-0hi_?utm_source=share&utm_medium=member_desktop&rcm=ACoAAABTmhYB--4z1kd8jhB7eGE93gxPaEFahDo

But Japan is not just about geometry. It has also pioneered knowledge-driven PLM. A new generation of startups like PRISM by Things in Tokyo focuses less on 3D models than on capturing dispersed engineering know-how and using AI to retrieve and apply it. In a society where manufacturing knowledge is often tacit and held by veterans on the shop floor, this is not just a convenience — it is a survival strategy.

The Japanese story is thus one of continuity: from kernels ensuring precision to PLM systems designed to preserve collective craft knowledge for future generations.

South Korea: Fashion as Digital Twin

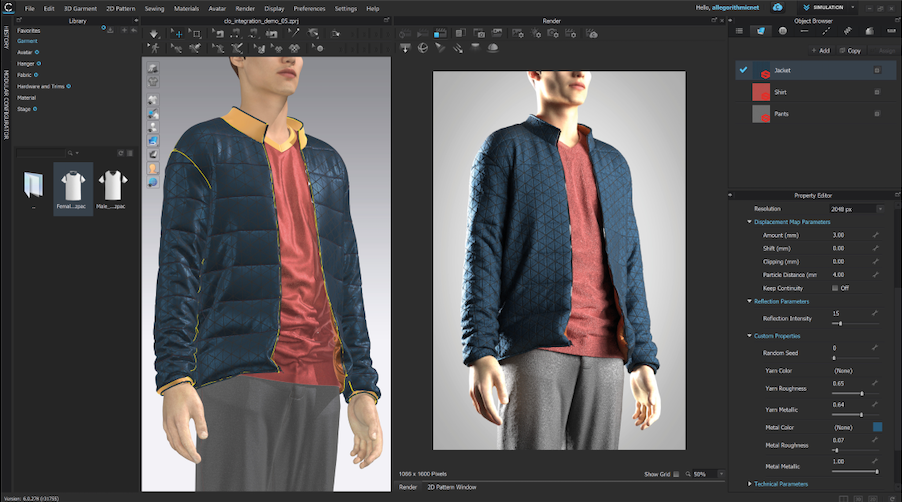

If Japan’s gift to PLM was precision, Korea’s was speed. Few industries move faster than fashion, and Korea turned this into an advantage by digitizing garments long before “digital twin” was a buzzword.

CLO Virtual Fashion, with its CLO3D and Marvelous Designer products, transformed how designers and apparel brands work. By simulating drape, stretch, and fabric physics, CLO allowed fast-fashion companies to replace physical samples with digital ones. That in turn pushed apparel PLM to evolve — managing digital assets, trims, and size curves with the same rigor as aerospace manages BOMs.

In an irony, it was the softest of industries — clothing — that forced PLM to become harder, faster, and closer to the consumer internet than any aircraft manufacturer ever could.

India: The Services Powerhouse

Where China and Russia invested in sovereignty, India invested in services. From the 1990s onward, Indian firms became the global back-office of CAD and PLM deployment. Tata Consultancy Services (TCS), Infosys, and Wipro ran massive programs to implement Teamcenter, ENOVIA, and Windchill for Western OEMs.

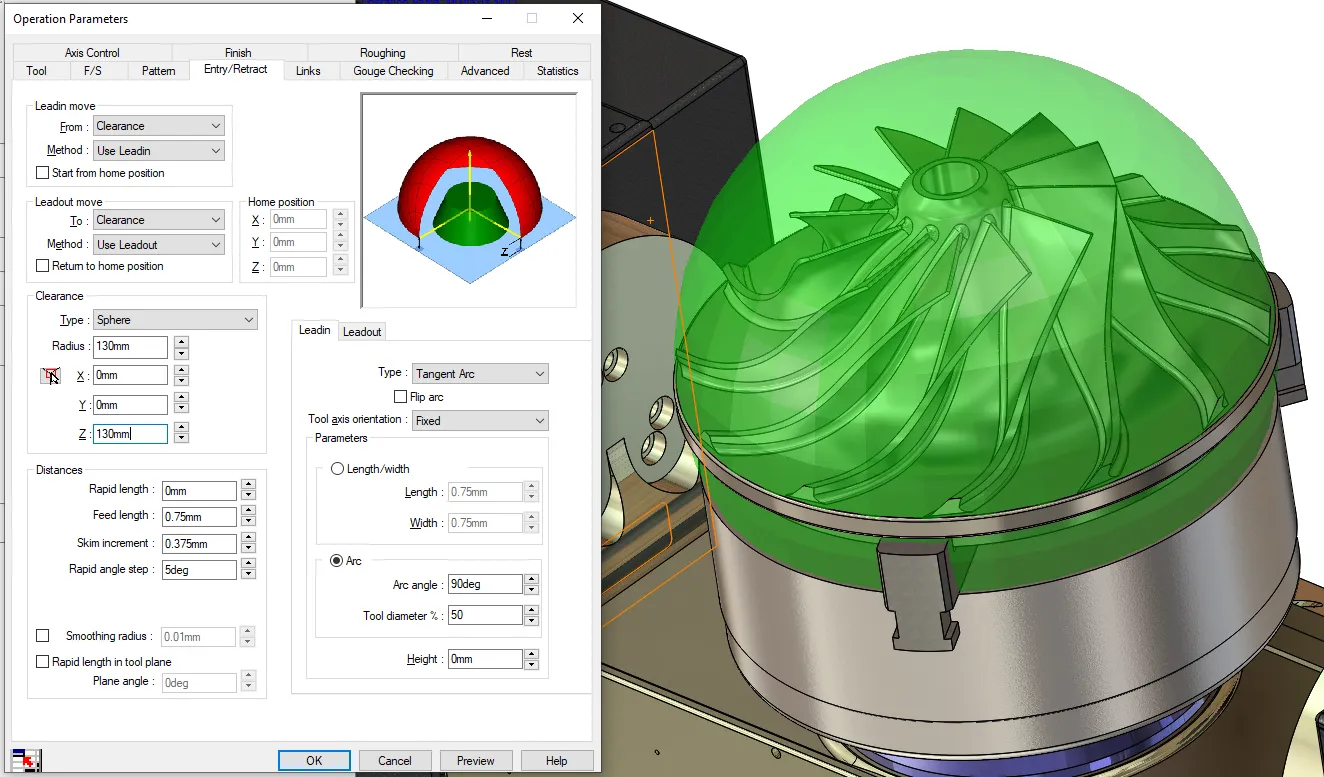

But India did not stop at services. In 2016, HCL Technologies acquired Geometric Ltd., a specialist in engineering software. This gave HCL control of CAMWorks, a respected machining platform, and signaled that Indian firms wanted intellectual property as well as service revenue. Today, CAMWorks sits inside HCLSoftware, while India’s SI giants continue to dominate global PLM rollouts.

India’s role is clear: if America invents, Europe integrates, and China secures, India scales. Its armies of engineers make the digital thread executable across the world’s supply chains.

Australia and Africa: Mining the Digital Thread

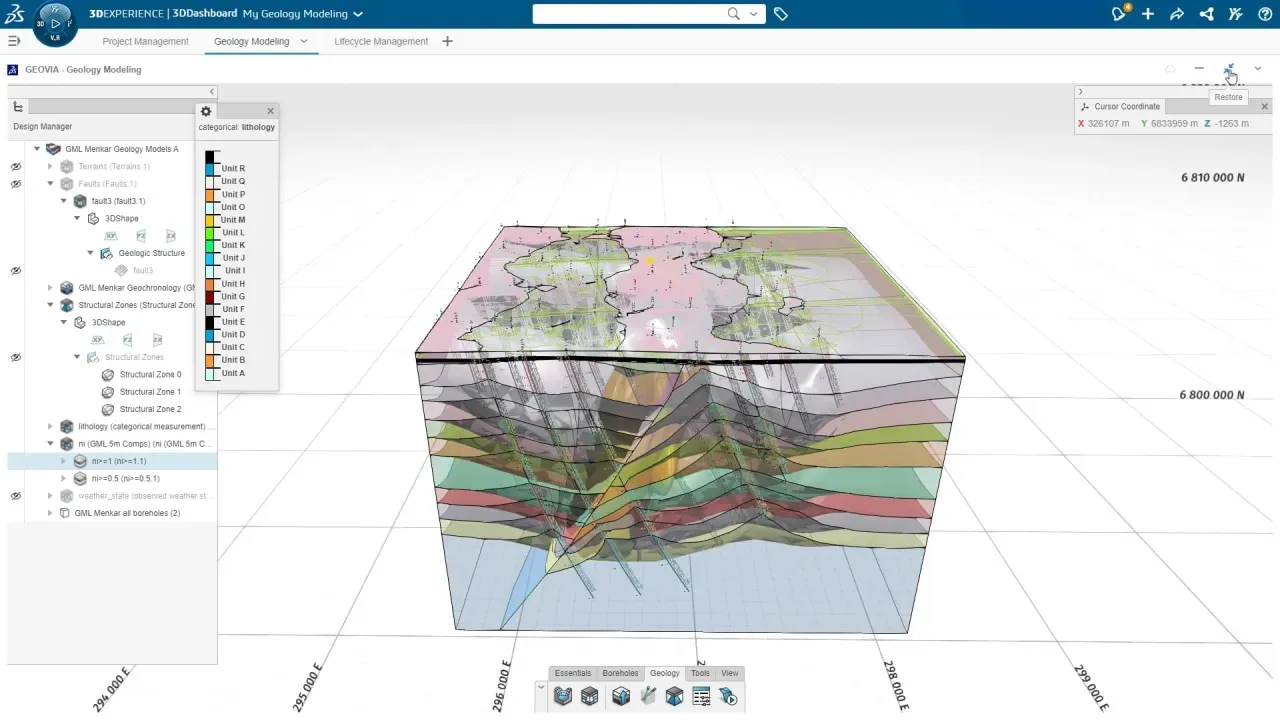

If aerospace shaped PLM in the U.S. and automotive shaped it in Europe, mining has been the crucible for Australia and Africa.

Australia gave rise to firms like Maptek, Micromine, and RPMGlobal, all focused on geology, mine planning, and fleet economics. In 2012, Dassault Systèmes bought Canada’s Gemcom and rebranded it GEOVIA, explicitly to gain entry into this vertical. Africa, with its vast mineral wealth, became a key market.

Mining forced PLM to extend beyond factories and into the earth itself — modeling not just products, but ore bodies, pits, and reclamation plans. In doing so, it showed how lifecycle thinking could apply to industries far from Detroit or Toulouse.

Israel: The Startup Nation’s Gift to PLM

Perhaps no country outside the U.S. and Europe has had as outsized an impact on PLM as Israel. Its story is one of relentless entrepreneurship, global partnerships, and strategic exits.

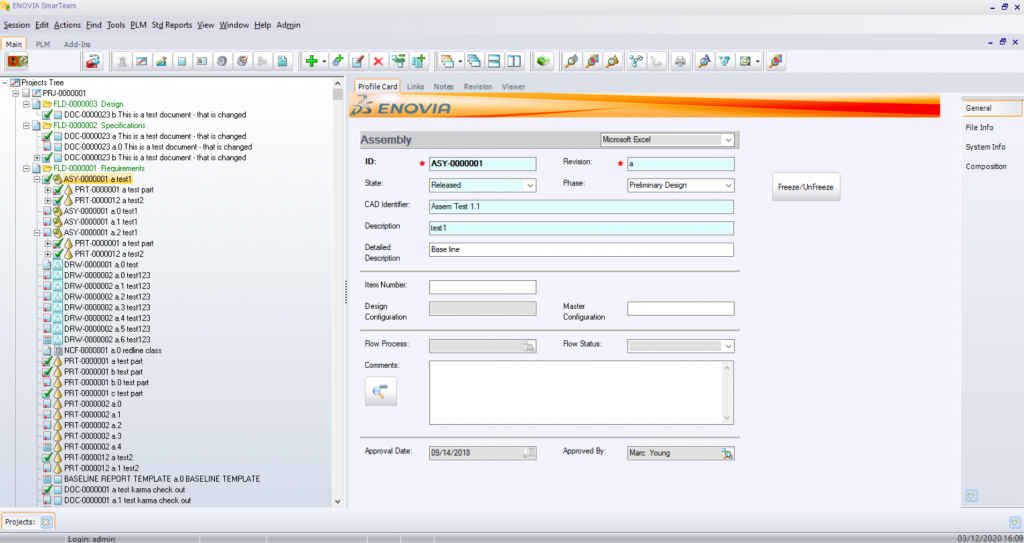

SmarTeam, founded in 1995, democratized PDM for small and medium manufacturers with a Windows-based client/server approach. Dassault Systèmes acquired it in 1999, folding it into ENOVIA and giving many suppliers their first structured product data system.

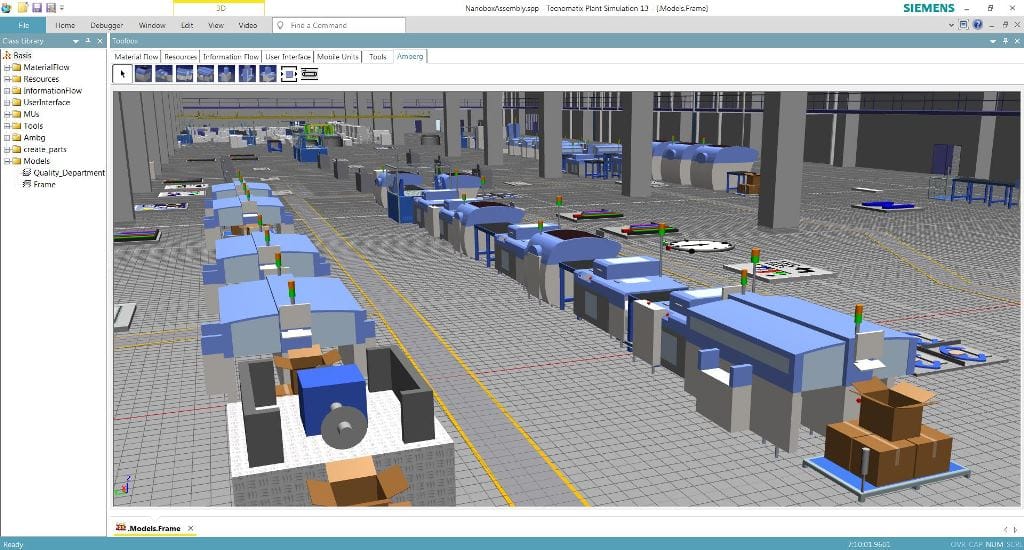

Tecnomatix, founded in 1983, anticipated the entire digital manufacturing wave. Its factory simulation software let automakers and electronics firms model assembly lines long before “digital twin” was coined. Siemens bought it in 2005, embedding Israel’s vision of smart factories into its global PLM portfolio.

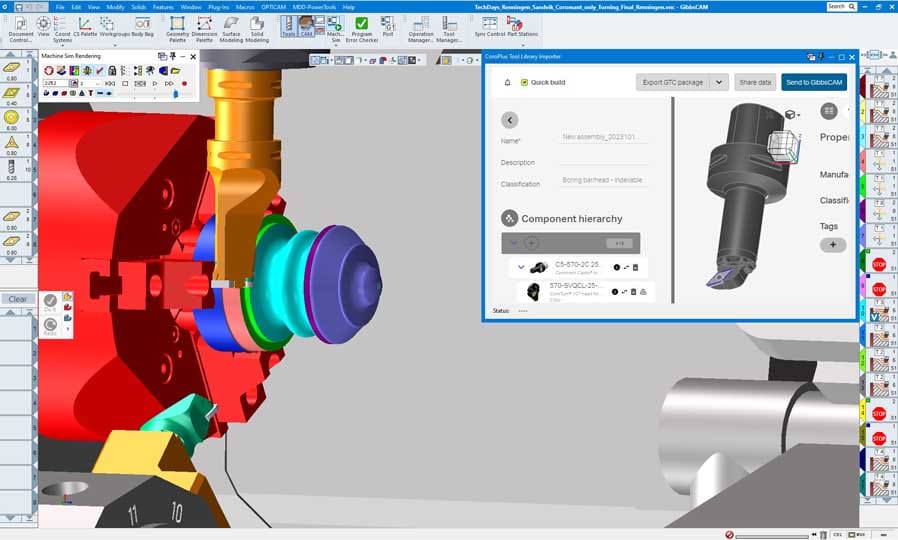

Cimatron, founded in 1982, became Israel’s CAM champion. In 2008 it acquired California’s GibbsCAM, and in 2015 the combined entity was itself acquired by 3D Systems, before ending up with Hexagon of Sweden in 2020. That means Israeli IP still powers one of the two dominant CAM systems in use today.

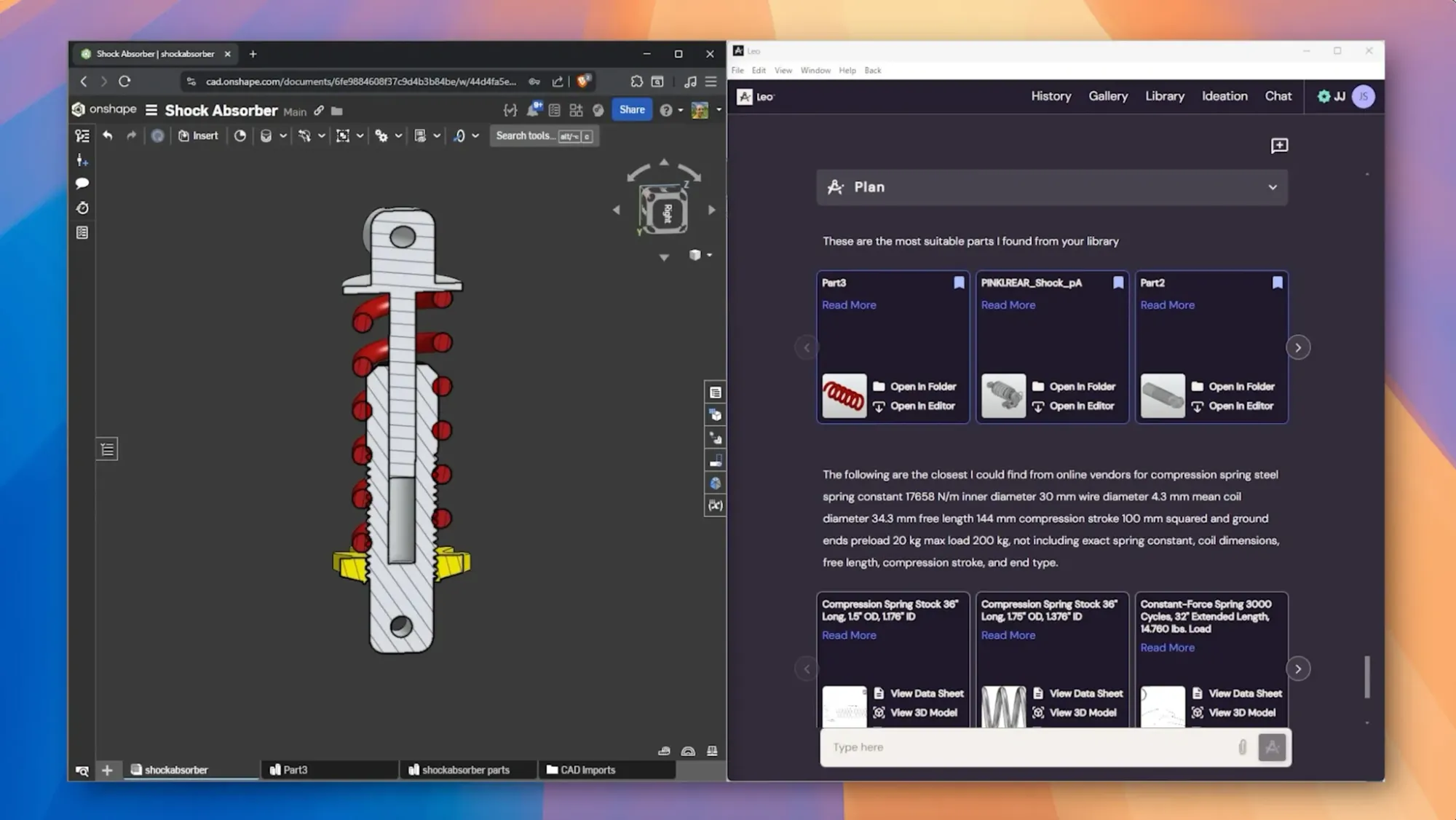

And the story continues. Startups like Leo AI are now applying generative and agentic AI to engineering, designing assistants that augment, rather than replace, human engineers.

Israel’s pattern is unmistakable: it does not build giant incumbents, but it creates ideas and products so valuable that Siemens, Dassault, or Hexagon cannot resist. Each wave — PDM, digital manufacturing, CAM, and now AI — has carried an Israeli signature.

Closing Reflections: The World Beyond the West

What emerges from this tour is a more balanced map of PLM’s evolution.

- In China and Russia, sovereignty is the driver.

- In Japan and Korea, precision and speed shape unique verticals.

- In India, scale makes PLM executable.

- In Australia and Africa, mining extends lifecycle thinking to the earth itself.

- And in Israel, relentless entrepreneurship injects new ideas into the global bloodstream.

If Boston, Paris, and Stuttgart wrote the first chapters of PLM, then Guangzhou, Tel Aviv, Tokyo, Seoul, Bangalore, and Perth have written the latest. Together, they remind us that the future of engineering software is not confined to a single corridor or continent — it is a global project, shaped by local needs and national ambitions, but converging on a shared goal: to make the lifecycle of products, processes, and resources visible, governable, and intelligent.