PLM History 101: PDM (Part 1) - Evolution of Assembly Modeling into PDM Systems - PTC (1980s–1990s)

Early CAD Assemblies and the Rise of Data Management (1980s)

In the 1980s, CAD software began to support 3D assemblies, but managing the many files and relationships of a complex product was largely a manual or ad-hoc process. Engineers often relied on naming conventions and printed BOMs to track which part went where. Large aerospace and automotive firms, running CAD on mainframes or UNIX workstations, started to develop custom databases to control their CAD files and bill-of-materials. These early efforts foreshadowedProduct Data Management (PDM) – a new class of software aimed at keeping track of CAD models, versions, and assembly structures. By the late 1980s, the need for systematic CAD data management was evident, setting the stage for commercial PDM solutions in the 1990s.

PTC’s Pro/PDM and the First CAD PDM Systems (Early 1990s)

One early milestone came from Parametric Technology Corporation (PTC). PTC’s flagship CAD, Pro/ENGINEER, launched in 1988 and quickly gained popularity for its parametric, feature-based modeling. To complement Pro/E, PTC introduced Pro/PROJECT, a basic project data manager, soon followed by a more robust system called Pro/PDM(Parametric Design Manager). Pro/PDM, introduced in the early 1990s, was PTC’s first true PDM software for CAD data. It allowed engineers to store and manage Pro/ENGINEER part and assembly files in a central vault, track versions, and enforce simple access controls. Importantly, unlike Pro/PROJECT, Pro/PDM could operate without an active Pro/ENGINEER license – it was a standalone data manager that a whole department could use. PTC envisioned Pro/PDM as a department-level PDM solution, suitable for a single project or workgroup, while larger, enterprise-wide needs might still be met by third-party systems of the day. At this stage, assembly modeling data – which includes the hierarchy of parts, their relationships, and positions – was managed in a fairly rudimentary way. Pro/PDM stored the files and recorded which parts were used in which assemblies, but it provided only basic support for part reuse or cross-project sharing. Still, it was a crucial step: engineers now had a central “vault” to prevent loss or overwrite of CAD files and could check-out assemblies knowing all referenced parts were the correct versions.

Other CAD vendors were also exploring PDM in the early 1990s. Companies like Intergraph and Computervisionoffered add-on data management tools, and independent PDM software firms (e.g. Sherpa, Workgroup Technology) emerged. Nonetheless, PDM was still in its infancy – often a glorified file manager with some BOM (bill-of-materials) listing capability. Assembly relationships in these early systems were typically inferred from the CAD files themselves. For example, an assembly file would contain references to its component part files; the PDM system’s job was to maintain those references when files were renamed or moved, and to list the components in a structured BOM view. Spatial positioning (the orientation/position of parts in the assembly) was usually stored inside the CAD assembly file, not separately in the PDM database. If an engineer opened a stored assembly, the CAD software would fetch the needed part files from the PDM vault and then apply the mates or transforms defined in the assembly file to arrange the parts in 3D space. While early PDM tools didn’t explicitly manage 3D positions, they ensured that an assembly always pulled in the correct parts – a foundational requirement for any assembly management.

The Mid-1990s: Enterprise PDM Emerges (PTC Pro/INTRALINK)

By the mid-1990s, the size and complexity of CAD datasets had grown dramatically. Companies were modeling entire vehicles, aircraft, and industrial machinery in 3D, producing “mountains of information” that needed careful management. This drove a new wave of PDM innovation aimed at enterprise-wide solutions. PTC, realizing Pro/PDM was not scalable enough, embarked on a next-generation PDM project. Internally code-named “Delta,” PTC developed a new, information-centric API and architecture for data management. The result was Pro/INTRALINK, introduced in 1997 as a more sophisticated approach to managing Pro/ENGINEER data.

Pro/INTRALINK was one of the first CAD PDM systems to use a client–server database architecture. It combined a central relational database (built on Oracle) with local databases on each user’s workstation. The central repository – aptly named “COMMONSPACE” – tracked all design iterations, assembly relationships, and configurations in a single source of truth. Meanwhile, each user had a personal “WORKSPACE” on their local machine for active work. This architecture let engineers work independently (using fast local disk access) and then seamlessly synchronize changes to the common server. For example, simply saving a CAD model would update the local workspace database, and when the user was done and closed the session, Pro/INTRALINK would update the central COMMONSPACE with the new iterations. All of this happened largely transparently to the user – a big usability win at the time.

Crucially, Pro/INTRALINK understood and managed assembly hierarchies. If a designer saved an assembly, the system knew to capture not just the assembly file but its dependency tree of parts and sub-assemblies. The Oracle-based COMMONSPACE recorded these parent–child relationships in a way that made querying and reusing parts far easier. Engineers could search the vault to see where a given part was used (which other assemblies), fostering part reuse rather than duplicate modeling. The system also enforced revision control: each save created a new iteration, and assemblies could be configured to use specific revisions of components, ensuring stable, reproducible builds (a concept known as configuration management). In fact, PTC built Pro/INTRALINK to handle not only CAD data management but also version control concepts borrowed from software development – it even covered some “software source control” functionality in tracking changes.

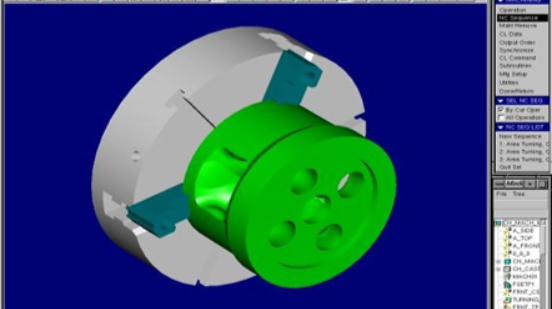

To aid with large assemblies, PTC introduced lightweight visualization in the PDM: whenever a Pro/E model was saved, Pro/INTRALINK generated a tiny bitmap thumbnail of the part or assembly and stored it in the database. Later, when users browsed the vault, they could see instant preview images of components, making it much easier to identify parts at a glance. This was an early step toward today’s rich DMU (Digital Mock-Up) capabilities – even without loading a heavy CAD file, the PDM could give a visual cue of each item.

By moving to a modern client/server design, Pro/INTRALINK dramatically improved how assembly data was managed. It ensured that spatial positions and mating relationships (still defined within the CAD assembly file) were always linked to the correct version of each part. For example, if a part was revised (say a hole moved), that new version wouldn’t automatically replace the old one in approved assemblies unless an engineer intentionally updated the assembly’s BOM to include it – preventing unwanted surprises. This kind of controlled evolution of assemblies was a hallmark of late-90s PDM. The only drawback was the complexity and cost: Pro/INTRALINK was expensive (list price around $5k per seat) and initially lacked easy migration tools for legacy Pro/PDM data. It took PTC until 1998 to provide reliable migration utilities, and only then did Pro/INTRALINK achieve feature parity with the old Pro/PDM system. Despite those early hiccups, Pro/INTRALINK was a leap forward, pointing the way to truly integrated CAD/PDMwhere large assemblies could be handled with confidence.

Around the same time, other PDM solutions were also tackling large-assembly management. Notably, SDRC (Structural Dynamics Research Corporation) had its Metaphase PDM (mid-1990s), and companies like EDS and IBM were developing enterprise PDM offerings. In fact, by the late ’90s industry observers saw PDM as the next battleground: PTC’s own CEO Dick Harrison was on record calling data management essential to becoming a billion-dollar company. The stage was set for PDM to evolve from basic CAD file control into a cornerstone of enterprise engineering IT.