PLM History 101: PDM (Part 2) Evolution of Assembly Modeling into PDM Systems - Unigraphics (1990s–2000s)

UGS iMAN: Distributed Assembly Management (Late 1990s)

In parallel with PTC’s efforts, Unigraphics Solutions (UGS) – the company behind Unigraphics (later NX) CAD – was forging its own path in PDM. UGS introduced a system called iMAN, short for “Information Manager,” in the mid-1990s. From the start, iMAN was designed as an enterprise-grade PDM with a very strong data model for assemblies and product structures. The system’s architecture was praised for its robustness: iMAN had an “extremely strong data architecture” that could support distributed teams, with excellent integration to Unigraphics CAD while also handling data from other systems. In essence, UGS built iMAN to be the backbone of product information in large organizations, not just a departmental tool.

By 1997, UGS released iMAN Version 4, and with it a groundbreaking feature: Distributed iMAN (D-IMAN). D-IMAN tackled a common late-90s challenge – how to manage CAD and assembly data across multiple sites or factories. Rather than force everyone onto one monolithic server, D-IMAN allowed a federation of databases. Each site ran a local iMAN database for performance, but a central Object Directory Service (ODS) acted as a master index of all data across the enterprise. If an engineer in one location needed a part designed in another, they could perform a remote search; the ODS would locate which site’s vault had it. Behind the scenes, D-IMAN would then retrieve or replicate the necessary data. Replication was controlled and selective, often scheduled during off-hours, to keep all sites in sync without bogging down networks. This federated approach meant even global companies (like an automotive OEM with design centers in Detroit, Germany, and Japan) could work from a common product dataset. Assemblies could be composed of parts from any site, and iMAN would ensure that when the assembly was opened, all the referenced parts – wherever they originated – were available. In practical terms, it enabled part reuse globally: the same fastener designed in one plant could be reused in another plant’s assembly simply by referencing it in the BOM, confident that iMAN’s distributed vault would deliver the correct geometry.

UGS didn’t stop there. In 1998, iMAN Version 5 came out with further enhancements to D-IMAN and, notably, new web-based capabilities. UGS added a web-browser client interface, making iMAN “web-enabled” and reducing the need for heavy desktop client installs. This was forward-looking: by using standard web protocols, iMAN v5 allowed different types of client machines to access the vault through a thin layer, hinting at the PLM systems to come in the 2000s. UGS even offered a slimmed-down PDM called UG/Manager (essentially a light version of iMAN) for smaller workgroups, but iMAN was positioned as the full enterprise solution.

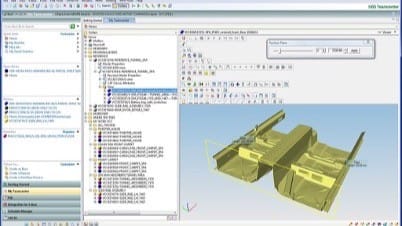

From an assembly modeling perspective, iMAN was very sophisticated. It treated parts and assemblies as first-class objects in a database. Each assembly knew its components (and their revisions) as database relationships, not just file links. This meant iMAN could do things like impact analysis – e.g. “show me all assemblies that will be affected if Part X is superseded by a new version.” This strong relational foundation gave iMAN an edge in configuration management. Complex products often have multiple variants and evolving versions; iMAN could maintain different BOM variants, effectivity dates, and change histories all within its data model. In addition, because UGS owned Parasolid (the geometry kernel) and had deep CAD expertise, iMAN integrated tightly with CAD functions. For instance, whenever an assembly was saved in Unigraphics, the system would update the PDM with the assembly structure automatically. And like its peers, by the late ’90s iMAN was investing in visualization: UGS developed lightweight JT format viewers, so that even without loading a full CAD session, users could navigate an assembly’s structure and see a 3D approximation for review or discussion. All of these capabilities made iMAN a cornerstone in some large corporations’ engineering IT. General Motors, for example, signed a huge contract with UGS around 2000, deploying tens of thousands of iMAN seats as part of a global PLM initiative. (Meanwhile Ford and others were backing SDRC’s Metaphase – signaling that PDM had truly become mission-critical for automotive assemblies.) After the Siemens acquisition, in 2007 iMan was renamed Teamcenter Engineering.