PLM History 101: PDM (Part 6) - Toward PLM and the Digital Thread

From the 1980s to the 2000s, we see PDM evolving from simple file control into something much more ambitious. By the early 2000s, the distinction between PDM (managing CAD data) and PLM (Product Lifecycle Management) started to blur. The systems from PTC, UGS/Siemens, Dassault, and others were expanding in scope beyond CAD. They began to encompass requirements management, manufacturing process data, even after-sales support information – all tying back to the product definition. In essence, managing CAD assemblies became just one part of managing the entire product.

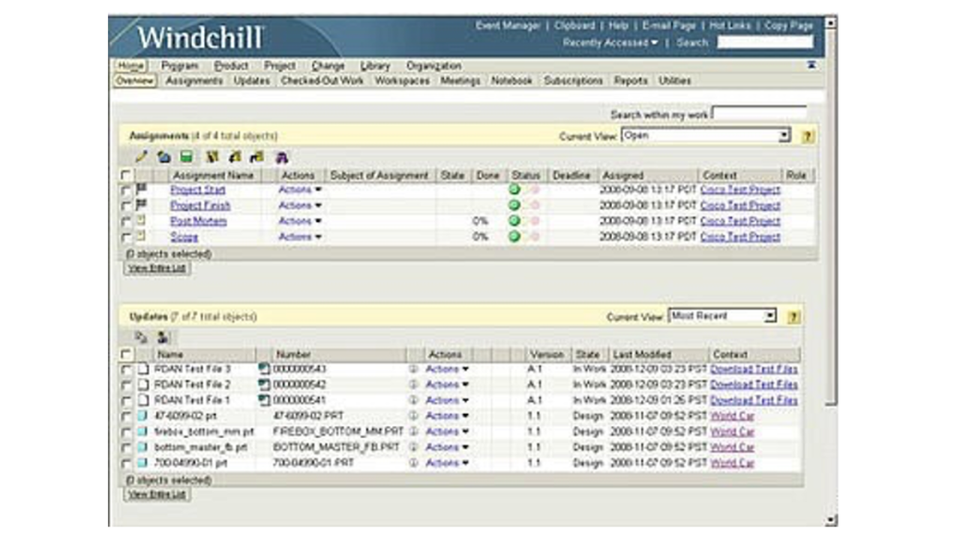

Several key developments around the turn of the century illustrate this convergence. PTC, for example, launched Windchill in 1998–1999, a web-native system aimed at enterprise PLM. Windchill initially complemented Pro/INTRALINK and eventually superseded it, bringing PDM onto the internet and into browsers. UGS and SDRC (the creator of Metaphase) were brought together under the EDS umbrella in 2001, and their technologies merged to form Teamcenter, which by the mid-2000s became a leading PLM platform combining the best of iMAN (now Teamcenter Engineering) and Metaphase (Teamcenter Enterprise). Dassault, for its part, continued developing ENOVIA and SmarTeam, and later introduced the 3DEXPERIENCE platform – an even broader vision of integrating design, simulation (SIMULIA), manufacturing (DELMIA), and data management. All these moves were about ensuring that every aspect of a product’s lifecycle – from initial concept and CAD design through analysis, manufacturing, and into service – could be traced and managed. This is the origin of the modern concept of the Digital Thread.

Today, the digital thread refers to an integrated data flow that connects every phase of the product lifecycle, often across different software tools and organizational silos. As defined in one industry context, a digital thread is “an integrated system that connects data from all facets of an operation and enables sharing between different areas”, ultimately providing a holistic view of the product across its lifecycle. The PDM and PLM systems of the ’90s and 2000s laid the groundwork for this. By getting CAD and assembly data under control, they made it possible to link that data to other domains. For example, once a CAD assembly and its BOM were managed in a database, it became possible to automatically feed the BOM to an ERP system for ordering parts, or to connect a requirement document from a systems engineering tool to a specific part in the CAD model. The digital thread extends these connections so that ideally every piece of information – CAD models, analysis results, shop floor machine programs, quality reports, maintenance logs – are all connected back to the digital definition of the product.

Looking back at the evolution from the 1980s through the 2000s, we can appreciate the key milestones. PTC’s Pro/PDM introduced the idea of CAD data management integrated with CAD software. UGS’s iMAN demonstrated how to scale that idea to a global enterprise and multiple CAD systems. IBM/Dassault’s VPM brought PDM into the heart of complex 3D products like airplanes, ensuring that huge assemblies could be navigated and controlled. Mid-market tools like Autodesk Vault and SolidWorks PDM democratized those capabilities for everyday engineers. Along the way, these systems mastered the fundamentals of assembly management: part reuse (one digital part used in many assemblies without duplication), spatial positioning (preserving how parts fit together in 3D space), BOM structure (hierarchical relationships of assemblies/sub-assemblies/parts, often mirroring the product structure), and revision control (so that changes are tracked, and past configurations can be retrieved exactly as they were). Each generation became more sophisticated in handling these aspects – from basic file locking in the early days to full configuration and change management in later years.

By the end of the 2000s, PDM had essentially evolved into PLM. The systems were not just vaults for CAD, but the backbone of product development and beyond. Engineers, managers, suppliers, and even customers could be looped into the product data via workflows and web portals. The Digital Thread concept builds directly on this foundation: since all the data is managed and connected, one can trace a line (a “thread”) from an initial requirement to a CAD model, from the CAD model to a tooling design, from there to a manufacturing plan, then to an inspection report, and onwards to field performance data – all linked. Achieving this ideal is still a work in progress in many industries, but the trajectory is clear. The pioneering PDM solutions of the late 20th century provided the single source of truth for CAD and assembly data, without which the larger vision of an end-to-end digital enterprise would falter.

In conclusion, the period from the 1980s through the 2000s saw assembly modeling and PDM grow up together. What began as simple attempts to avoid losing track of files blossomed into sophisticated platforms that underpin modern engineering. Assemblies – the building blocks of products – can now be managed in databases with millions of parts, across continents, with full traceability of every change. This evolution not only improved CAD data management but fundamentally changed how products are developed: enabling concurrent engineering, global collaboration, and the confidence that comes from knowing the right data is in the right place at the right time. It set the stage for today’s PLM environments and the emerging digital thread, in which a product’s digital life mirrors and guides its physical life from cradle to grave. The journey of assembly modeling into PDM systems is a story of increasing integration, scale, and scope – an unsung hero of the digital revolution in manufacturing, quietly ensuring that all the parts (literally) come together in the end.

Next series up: PLM - The rise of the monoliths!